Ten Principles of my GCSE PE Classroom with my Yearly Plan 2022/23 Part 1

The aim of this week’s and next week’s posts is to share with colleagues the essential concepts by which I teach my PE classes. I have chosen to use an example from Edexcel GCSE PE this week and I will focus on AQA GCSE PE next week, but these principles can be applied to any PE course where an exam is taken. I refer to my model as The High Impact PE Classroom. Done well, this model outperforms every other classroom model out there and I urge PE teachers to seriously consider incorporating elements of the model or the model itself in a timescale that suits them.

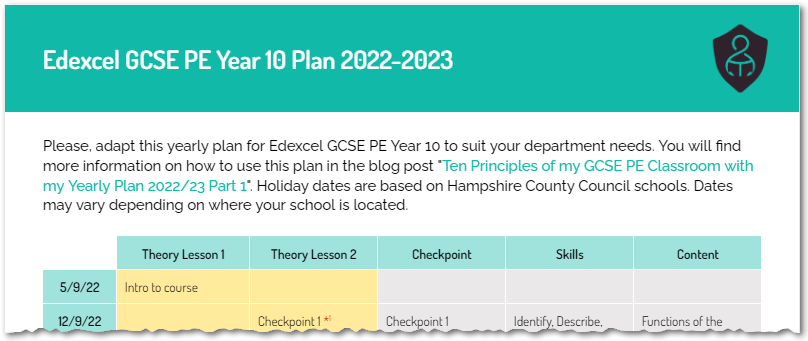

Key language from the yearly plan

| "Theory Lesson" | A classroom-based lesson with a nearby practical space available when required. |

| "Checkpoint" | A mini summative assessment and data extraction. This could be a checkpoint on TheEverLearner.com but is most commonly a series of exam-style questions from ExamSimulator. |

| "Skills" | The desired writing/drawing/calculating skills required on this course. |

| "Content" | Domain-specific knowledge and understanding |

I would like to remind colleagues that one of my core working aims is to dramatically improve the raw-mark performance of PE students in PE exams and it is for this reason that I am sharing these ideas as an attempt to promote better learning for everyone.

I hope you like it 😎

My Ten Principles

- The classroom is for learning more than it is for teaching.

- Student academic/exam “ability” is unknown and unknowable.

- It is inappropriate to “teach to the spec”. My role is to teach to the breadth of a potential mark scheme for the specification.

- High-quality homework is essential.

- PE classrooms must focus on skill development via the taught content, not the other way round.

In next week’s blog: - All PE content is taught through application rather than being taught and then applied later.

- Feedback must be received as soon after the learning/assessment activity as possible.

- Data comes in three tiers and tier 1 and 2 data is live and volatile and available continuously.

- Students work towards specific targets at all times.

- Every learning activity is diagnostic, with the exception of the final, external exam.

So, let’s start with the end in mind. Below you will see my yearly plan for Edexcel GCSE PE Year 10 2022/23. This plan can be downloaded below including an editable version so that you can make it relevant to you and your course. I will be included my plans for AQA and OCR GCSE PE in part 2 of this post next week. As you read through the ten principles, reconsider the impression of the yearly plan and why the features of it are the way that they are. My plan is very far from accidental. Every feature of the plan is carefully placed. The following ten principles will reveal these points.

Click the image to download a PDF of our plan.

If you want an editable copy, please click here (Google account required).

Principle 1: The classroom is for learning more than it is for teaching

I would like you to step back for a moment. In your recent planning episodes, to what degree have you focussed on your teaching behaviours and to what extent have you focussed on student learning behaviours? Of course, there are links between the two and there is nothing wrong with “teaching” but the point I want to make very clearly is that the only purpose of your classroom is to provoke the maximum learning possible in the broadest set of skills that is relevant. The extent to which you “teach” is not relevant unless that teaching behaviour is the best choice to promote the maximum learning. Now, this is not a woolly notion of “let’s keep them active” but, rather, an essential mentality to utilise every moment of your classroom time to promote learning.

Consider, for example, PowerPoint presentations. Are these genuinely high-quality learning experiences in your classroom? How often do you PowerPoint your students? What is the learning justification of choosing presentations? In my experience of teaching tens of thousands of PE lessons and observing hundreds, long presentations (often featuring pre-prepared bullet points of text) are extremely ineffective at promoting high-quality learning. Receiving a presentation is commonly a passive experience for students. I urge you to question why you use this methodology if, in fact, you do.

Now that I have “bashed” PowerPoints, let me be more proactive. I like to promote learning behaviours in my classroom. Highest on this list of behaviours is concentration. I urge every teacher to step back, once again, and ask what proportion of their classroom time is spent with students in deep concentration. This is the aim of my classroom: concentration! If students are concentrating, with world-class and highly relevant materials in front of them, learning is highly likely. Concentration is occurring when:

- Students cannot sustain it.

- Students ask not to be disturbed.

- Students need to move.

- The experience leads to pleasure or frustration.

Now, I would argue that this is not the list of behaviours that most teachers are looking for. These are the only behaviours that I seek (in relation to concentration). If I teach from the front, it needs to hit these needs too: pacey, demanding but inclusive.

So, in summary, my classroom is about learning. So much so that by the end of my course, I aim to be redundant in relation to the students’ learning.

Principle 2: Student academic/exam “ability” is unknown and unknowable

The word “ability” is banned from my classroom. It is also banned from any department I manage. It is also challenged in every interaction or meeting I have with teachers including my own line managers.

I want you to take a moment and think: what do you understand by the word ability? What does it mean to you? To me, it refers to an assumed set of innate, biological characteristics (in this case of the mind) and a preset capacity for learning. Is this close to your definition? If I was to challenge you to remove the word ability from your lexicon and replace it with “performance” and “behaviours” does it change anything within your descriptions of students?

I do make assumptions about ability on my courses. Here is the main one: student learning ability is unknown and unknowable and there is not a test in existence nor a teacher on the planet that can measure it. Here’s another: if there is such a thing as a biological marker of ability, I ignore it entirely because it is irrelevant to my classroom.

A good way to think about this is the notion of controllability. Student behaviours and performance are controllable. Between the student and the teacher, student performance can be stimulated and good learning behaviours can be promoted and reinforced. Whereas, ability is beyond our control. Therefore, I do not give ability any of my attention? Yes, there have been cases of severe learning disadvantage where exceptional effort has been required but the focus here has been on the structures and behaviours that lead to success.

For this reason, every student in my group is expected to master concepts and skills. Nothing less than that is accepted by them or by me. I open the space above the students and, with very few exceptions, the students grow to fill that space.

You may be wondering what I do with projected grades and standardised tests. The best summary I can give you is that I ignore them completely whilst fulfilling every protocol of my school/college.

Principle 3: It is inappropriate to “teach to the spec.” My role is to teach to the breadth of a potential mark scheme for the specification

Now, this one will irk a number of readers. Is James saying that his Edexcel GCSE PE teaching is not focussed on the requirements of that course? No! I am simply stating that our role as educators is to give every student the skills and knowledge to be able to access the broadest possible mark scheme, in this case, for Edexcel GCSE PE 1-9. I am also saying, categorically, that it is unacceptable to teach “up to a specification”. In the worst PE lessons I have witnessed, teaching “up to the specification" is occurring.

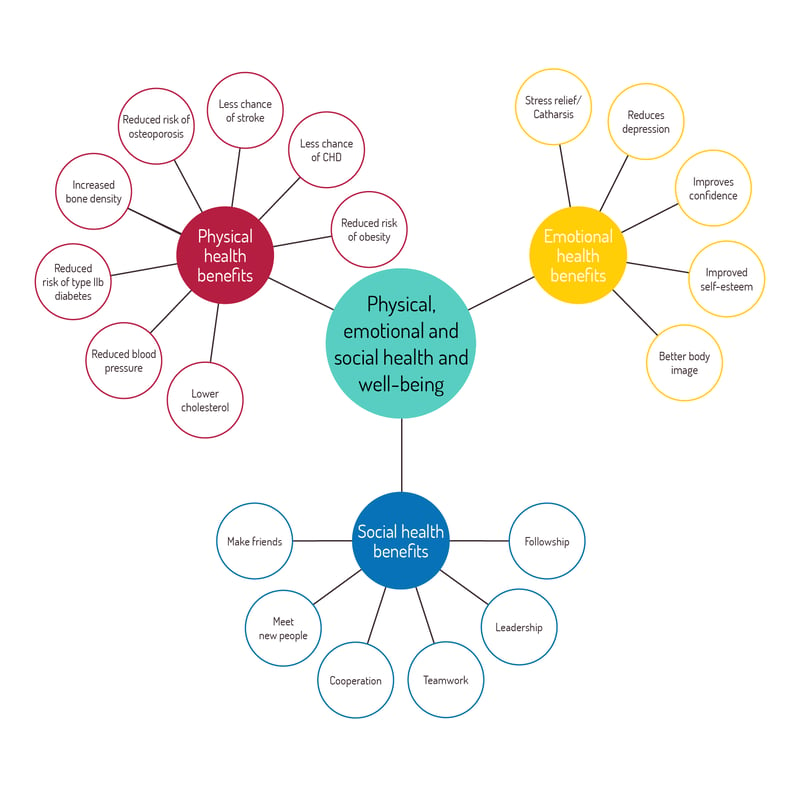

Let’s use an example. Below, you will see the exact accepted language for physical, emotional and social health and wellbeing from Edexcel GCSE PE 9-1:

In essence, if I were to tell the students these points, this is “teaching up to the specification.” When I look at images like this one, two simple questions spring to mind:

- Why?

- How?

My focus then becomes the “Explain” skill and, rather than teaching a list of physical, emotional and social benefits, I aim for the students to learn the explain skill in relation to these concepts. Furthermore, if we take a big step back, we presumably want the students to apply these principles to their own lives. By causing the learners to learn through the “explain how” frame, they develop knowledge of the actual behaviours and choices that cause better health.

Let’s take one example: “Regular exercise decreases the likelihood of osteoporosis.”

This learning is only relevant to learners if we consider the following:

- What is osteoporosis and why is it a problem? (Describe skill)

- Is it all types of activities that achieve this? (Explain how skill)

- Are there any negatives? What if we do too much of the activity? (Evaluate skill)

By addressing these points, students develop the capacity to explain and (with the last point) evaluate the idea as well as to look at the application of the knowledge. In other words, my teaching aim is the skill of explaining (and to a lesser extent evaluating) and the conduit to this skill is the “Benefits of exercise” topic. If you take a look in the week commencing 15th of May 2023, this is apparent based on the desire to develop these skills.

Principle 4: High-quality homework is essential

If anyone tells you that homework does not have an impact, thoroughly ignore them. What they probably mean is that low-quality homework does not have an impact. OBVS! On the other hand, high-quality homework, based on sound educational principles is highly impacting. Furthermore, as we are discussing the teaching of academic PE, we need to recognise that the subject receives limited curriculum time and is a significantly lower priority than other courses in most schools/colleges. Therefore, homework in PE is arguably more important than in some other subjects.

I set at least two homeworks every single week. I want to be clear: I set at least 104 homeworks per calendar year. There are no exceptions. Now, you may well have specific homework policies that prevent you from doing this exactly like I do but I am confident that, if you frame your wording of your tasks carefully, you can fall well within your school’s homework policy.

So, let’s look at a typical week’s homework. Remember: these are just examples and not a standardised homework structure:

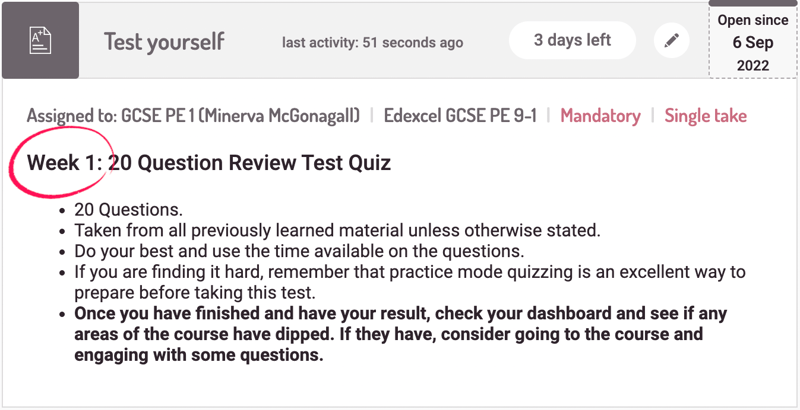

Task 1: 20 quiz questions from all material previously studied

This task is very simple and takes learners approximately ten minutes. I set the group 20 quiz questions per week, running from Monday pm to Monday am of the following week, and they are drawn from all learned material up to that point. For example, in Edexcel GCSE PE, my Week-1 task would only include:

- Functions of the skeletal system

- Classification of bones

- Structure of the skeleton

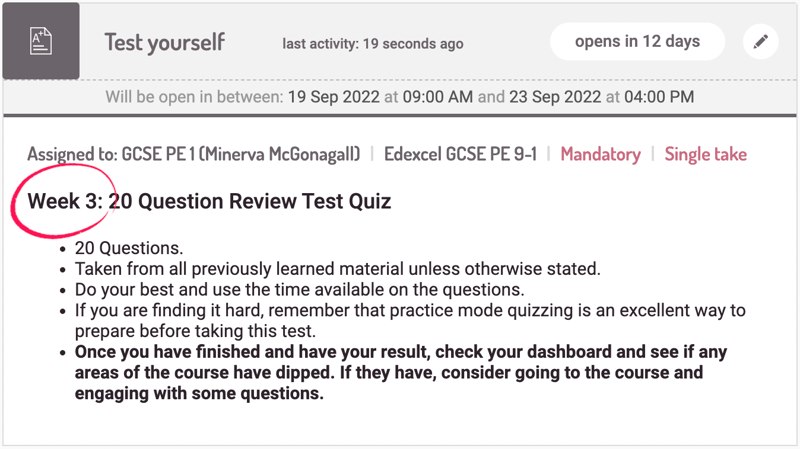

But, by week three, the 20 questions would be drawn from:

- Functions of the skeletal system

- Classification of bones

- Structure of the skeleton

PLUS - Joint types

- Joint structure and function

- Movement patterns

So, by September of 2023, the students will have answered 1040 quiz questions without me having to do any writing or marking and simply managing the outcomes. Furthermore, student knowledge and their profile of performance will be available to me via my dashboard. In other words, I can make intervention and remediation hyper relevant to my learners.

Consider the likely impact of students engaging with thousands of quiz questions whilst studying on your course. What might happen to their subject-specific vocabulary? What might happen to knowledge mastery? What might happen to their capacity to make better applications? What might happen to their tendency to forget older material?

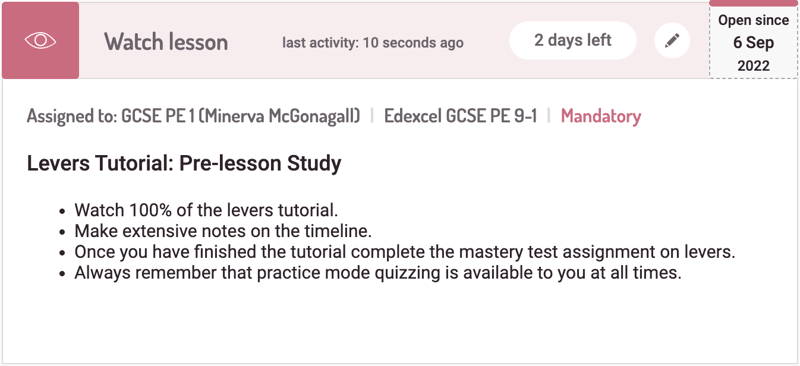

Task 2 example: Study one tutorial and master an eight-question test in advance of the upcoming lesson.

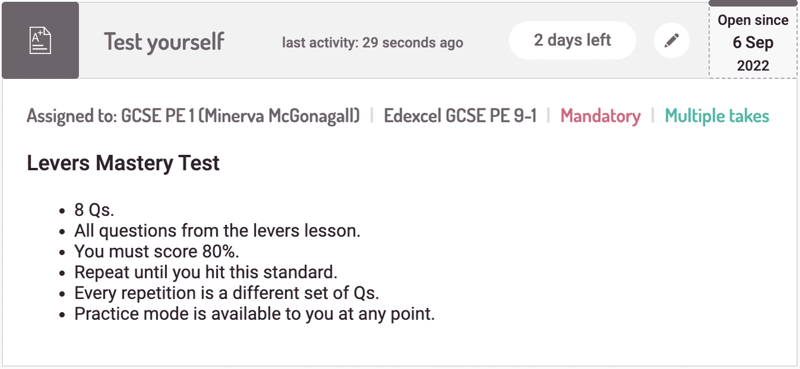

Now, my second task is much more varied than my first one (which is the same every week). In this example, I want to use some pre-loading. I am assuming that later this week I have a lesson with my group on levers, say. Therefore, in advance of that lesson, students are going to study a 10-minute tutorial on levers, make some notes and then prove to me that they have a fundamental grasp of the knowledge by mastering a very short test.

This then allows me to structure the lesson time with the application of knowledge as the focus rather than the development of core concepts. Here are the tasks I would set for students in this situation:

Pre-study 'Watch' assignment

Pre-study 'Watch' assignment

Pre-study mastery test

Pre-study mastery test

I’m sure that you will agree that this is a high-impact homework. But, also, that these tasks achieve a further crucial requirement: they are “skinny” homeworks - each task will take the student no longer than 10 minutes, meaning that in a standard week the students complete 30 minutes of homework per week.

Principle 5: PE classrooms must focus on skill development via the taught content, not the other way round

If you have read everything in this post so far, you probably have a strong sense of this principle already. My teaching aims focus on skills, not on content. Or, rather, I use content as a conduit to achieve skills, which are my primary aim. Many teachers approach the challenge in this way but I feel that my methodology differs because it is so fundamental to my practice.

I consider there are two sets of skills to develop with students:

Type 1: Exam skills

- Identifying

- Describing

- Explaining

- Analysing

- Calculating

- Evaluating

- Comparing etc.

Type 2: Broader skills

- Time management (attendance)

- Time management (punctuality)

- Time management (deadlines)

- Quality of written language

- Organisation

- Guidance and leadership

- Communication (listening)

- Communication (speaking/presenting)

- Coaching etc.

For the purposes of this post, I will focus on type 1.

Every two weeks of my yearly plan, I have identified a series of skills and a series of content that I wish to develop in the students. The fortnightly checkpoints are squarely focussed on these skills via that content. Because I have these skills identified, it makes it very convenient for me to build resources because the resources must address these skills. Otherwise, they are worthless. Furthermore, I make the intended skills explicit to the learners and they develop a broader familiarity of what they are and how to achieve them.

Once again, look at the two weeks commencing on the 8th and 15th of May in the yearly plan (editable version here - Google account required). Is there any doubt about what my students and I will be doing? Is there any doubt about the nature of the resources and the assessments we will use? Is there any doubt as to what I expect from learners? In my opinion, the answer to all three questions is “no”.

So, there we have it. The first five of my 10 principles of teaching academic PE. What are your thoughts? Do you agree? How does your practice differ from mine? Please, consider making a comment below. I always answer. 😊

Have a lovely day.

%20Text%20(Violet).png)